Parsa Khalili

Studio Lynn at Institute of Architecture / die Angewandte

Assistant Professor

The plan [section] is the generator.

Without plan [section], you have lack of order, and wilfulness.

The plan [section] holds in itself the essence of sensation.

The great problems of to-morrow, dictated by collective necessities, put the question of “plan” [“section”] in a new form.

Modern life demands, and is waiting for, a new kind of plan [section], both for the house and for the city.

Click and hold to rotate model. Click the comment icon to begin a guided tour.

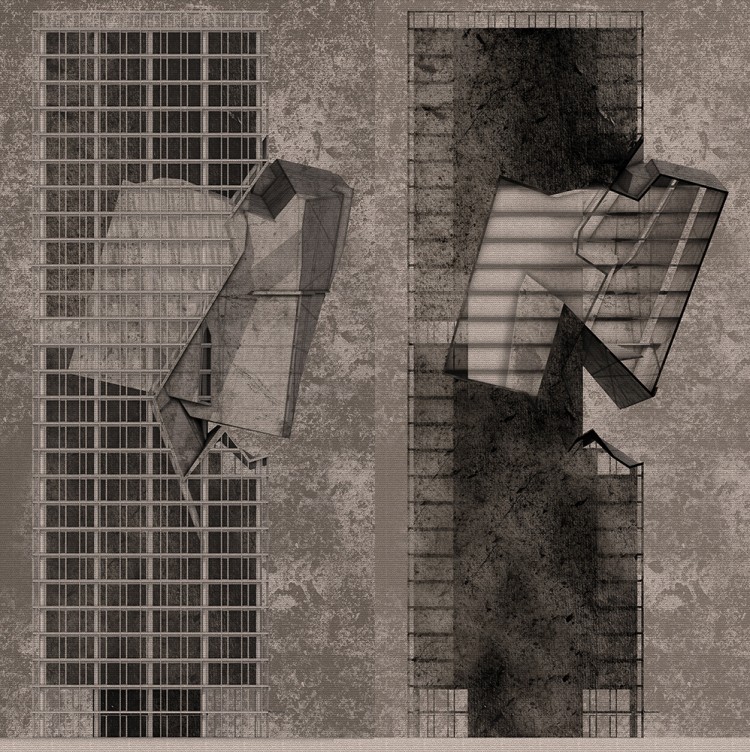

If in the first half of the 20th century, the city and its architectural byproducts were composed based on the tenets of modernism’s inception of the free plan, whereas the latter half of the 20th century saw a pervasive interest in the free section, the immediate future would seem to call for a radical development of the plan section. Although its thematic exploration occurred primarily in the 1980s, with speculative proposals from both deconstructivist architects and various purveyors of the then-emergent valorization of globalization as means to architecture, in its contemporary and post-contemporary turns a deeper and more critical interpretation and application of this means of organizing architectural space has emerged. Currently there exists a limited discourse on its implications within the verticality of today’s metropolis. The provocative nature of the work presented here aims to conceive of a late-late-modern cultural turn in the object-subject relations of the 21st-century city based on an alternate model for architecture’s presence within the “bland, anonymous, repetitive, empty, dispersive, vacuous, risible, [and] ‘post-existential’” landscape of the contemporary metropolis.

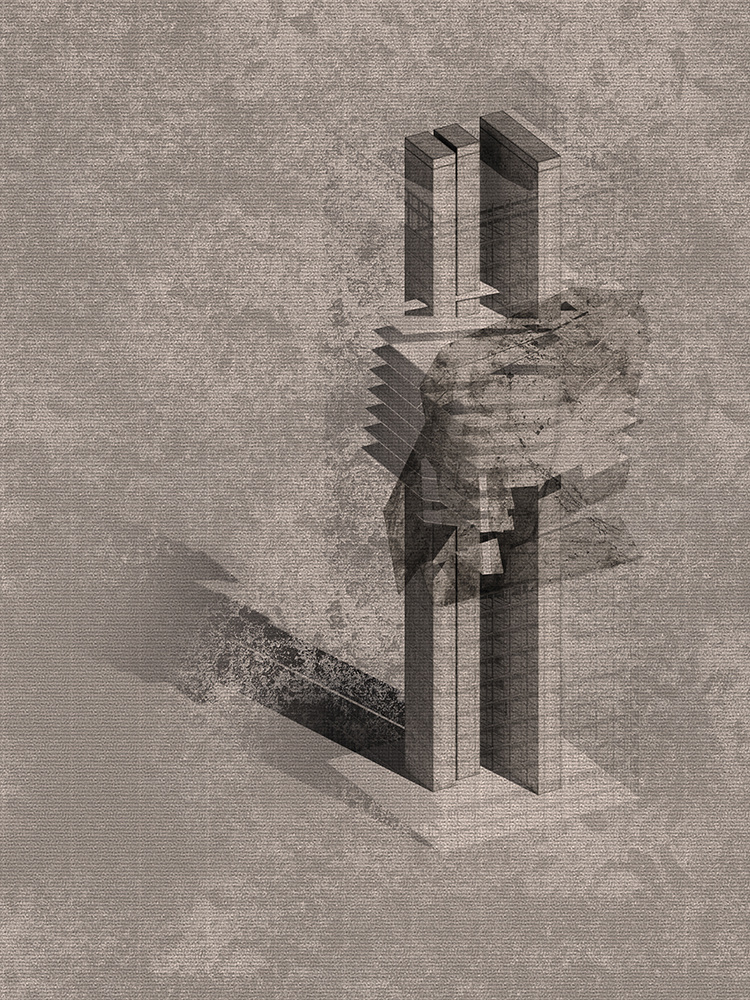

The site of the present investigation is, generically, “the metropolis,” yet specifically employed here on its most “genetic” level utilizing Giorgio Agamben’s description of urban fabric as fundamentally characterized by dishomogeneity,” a condition that “emerges in parallel with the processes of transformation … defined as the shift from the territorial power of the [ancien régime], of sovereignty, to modern biopower, that is in its essence governmental.” This reading of the city implies a radical shift from understanding it as classical polis, given that the contemporary problem of verticality implies or infers that which has no center (no agora), and thus a territoriality with no explicit, formal-political zone. As such,[Sectional Insurrection] gives form to the implicit differentiations latent within the abstract and homogeneous confluence of activities that instantiate the contemporary city. Such readings, and such projections, are indicative of a somewhat apocalyptic vision of so-called civil society, a 19th-century construction that has slowly broken down over the course of the 20th century, and which seems generally in tatters today with global inequality on the rise and systemic failure in multiple, interrelated cultural, environmental, and economic regimes just over the horizon.

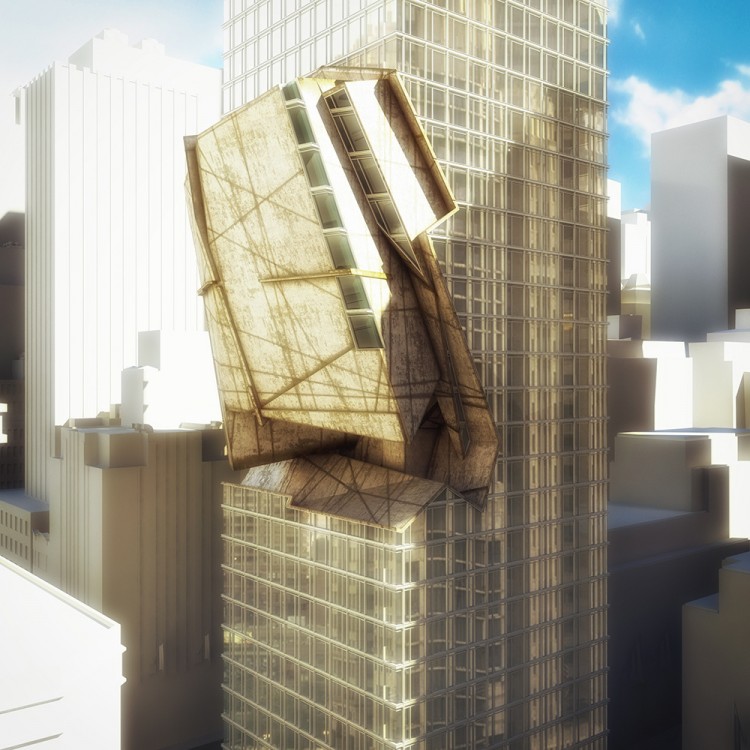

In the wake of concerns regarding metropolitan sprawl and the repurposing of urban fabric to better adapt to contemporary needs (for example, needs driven by the socio-economic and environmental dysfunction noted above and below), this project posits the idea that cultural icons need no longer be situated within planometric zones of the city, but rather can, paradoxically, find more fertile “ground” in the otherwise monotonous or banal vertical space that has developed above it. If we invert the historically derived notion of reading the DNA of the city at 90 degrees (via the grid), a practice dating back to the Romans, we are free today to imagine the architectural icon as something striated within the third dimension of the city proper and approaching a fourth dimension characterized by certain libidinal energies given to sci-fi film and literature. Unlike more traditional approaches to monumentality, this conceptual turn creates new relationships of building to ground by freeing the need for architecture to address normative issues of siting and its relationship to the city as a totality. Indeed, such aerial prospects are driven by the very abdication of ground (so-called civic space) to biopower and forms of repression. Atop this, we also have the increasing problem of environmental decay (pollution, extreme weather, etc.) driving architectural space further inward and, in many cases, upward.

Le Corbusier’s free plan, as canonized by the Maison Dom-ino prototype exactly one hundred years ago, has long been one of the most influential conceptual diagrams driving the development and critique of modernist architecture. This early transmutation of Le Corbusier’s diagrammatic method to built space opened the door to the possibility of new conceptual approaches to the creation of modernist and postmodernist architectural space. That the spirit of Maison Dom-ino crossed both the modernist and postmodernist approach to avant-garde architectural production also suggests that its formal operations reach very close to, or align with, the ultra-modernist project of altering the DNA of building after catastrophe – for example, and in the case of Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-ino, World War I.

The additional erasure of a direct relationship to the ground forces inhabitants of “genetically modified space” to forge new relationships to architecture and the city. Paradoxically, the purely exterior imprint of the project becomes something only visible from a distance, while the lived experience of its spatial byproduct becomes a purely interiorized phenomenon. The historically influential promenade architecturale is subsequently amputated and transformed into a binary “far” and “close” relationship with no “middle” experience to speak of. Indeed, it is this very “middle experience,” consistent with theories of civil society, that is being wiped out by current socio-economic, global trends. The figure of this new architectural-urban relationship thus needs to operate at two scales: the former, where architectural form and composition resonate with the urban image of its context (Kevin Lynch’s “imageability”); and the latter, where attempts to condense the larger urban terrain and its complexities into a purely interiorized sequence of spaces and exposures lead in the direction of the “unknown” (arguably, a dangerous but perhaps profitable mutation or bifurcation driven by the ravages of late-late-modern, post-contemporary culture).

[Sectional Insurrection], as represented here, is, therefore, merely a set of “working drawings” toward a prototype. The prototype would formalize new forms of architectural iconicity based on revolutionary tenets of organization and ultra-interiorized relationships to the city at large. In giving voice to a new cultural paradigm within the free section of the city, certain knock-on effects are obvious, though it should be clear that the juxtaposition is not purely parasitical. Or rather, such a provisional model is parasitical only in the manner of Michel Serres’ reinterpretation of Marx’s “exchange value,” or only insofar as the emergence of symbiosis produces new functionality and information in exchange for energy and infrastructure. Notably, Serres’ somewhat pseudo-Darwinian and dark adaptation turns an early anti-capitalist economic critique into an anthropocentric and linguistic critique, enabling the possibility of a parasite to be productive rather than purely destructive. It also acts to underscore the fact that the singular object of architecture (one of the great modernist fantasies) is a mythic construct, and that reciprocal relationships always already inform architectural forms, most especially when they are embedded in a milieu that carries explicit or implicit historical baggage. Given Agamben’s ongoing inquisition of modernity, it is more than evident today that this historical baggage is also the functional equivalent of the historical unconscious, and that it is precisely this luggage that is loaded with incendiary apparatuses that account for the diabolical state of global affairs today. In contrast to the conventional static verticality of the new metropolis, (formally, in terms of spatial operations, but also in terms of the people and the type of spaces they inhabit), the parasite oddly creates an altered sense of equilibrium – temporal or otherwise – that suggests cordoned-off space within space, mildly analogous to medieval impoundments. This transformation in representational thinking may retool the fading allure of 20th-century architecture’s compulsion with verticality and provide a new direction for its advancement aligned with non-hegemonic principles in opposition to the increasingly compromised prospects of externalized urban open space. It may be said, without irony or cynicism, that this project actually projects internalized urban open space.Text was produced with Gavin Keeney.